Researchers often struggle when choosing between ANOVA and a t test for quantitative data analysis. Both methods compare group means, yet they apply to different research designs and data structures. Selecting the correct procedure affects the validity of your findings and the credibility of your conclusions. Many thesis errors and rejected papers trace back to incorrect statistical test selection rather than wrong calculations.

Statistical choice depends mainly on the number of groups, the number of independent variables, and whether measurements repeat across time or conditions. These two techniques belong to the parametric testing family and share several assumptions, including approximate normality and equal variance across groups. Despite that similarity, their use cases differ in important ways.

This ANOVA vs t Test guide explains when to use a t test, when ANOVA becomes necessary, how one way and two way ANOVA differ from t tests, and where chi square fits in comparison. You will also see practical decision rules you can apply directly to survey and experimental research.

What a t Test Does in Quantitative Research

A t test evaluates whether the means of two groups differ beyond what random sampling error would explain. It works best when your dependent variable is continuous and your independent variable contains exactly two categories. Many academic and applied studies use this approach to compare treatment vs control, group A vs group B, or pre vs post measurements.

Statisticians use three common forms of the t test. The independent samples version compares two unrelated groups. The paired samples version compares two related measurements from the same participants. The one sample version compares a sample mean against a known benchmark value.

The calculation focuses on the ratio between mean difference and variability. Larger ratios indicate stronger evidence that a real difference exists. Output typically includes the t statistic, degrees of freedom, confidence intervals, and a p value.

This method remains efficient and powerful when your design truly contains only two groups. Once group counts increase, another method handles the structure more effectively.

Confused Between ANOVA and t Test?

Get expert guidance on choosing the correct statistical method for your thesis or survey data.

MSc & PhD data analysis support.

What ANOVA Does and Why Researchers Use It

ANOVA, short for Analysis of Variance, evaluates mean differences across three or more groups within a single model. Instead of running many pairwise comparisons, the method tests all group means together. That unified approach controls false positive risk and improves statistical rigor.

The procedure separates total variation into between-group and within-group components. It then computes an F ratio that shows whether group membership explains a meaningful portion of outcome variability. Larger F values indicate stronger group effects.

Research designs often include more than one factor. ANOVA supports those designs by testing multiple independent variables and their interaction effects at the same time. That capability explains why factorial experiments rely on ANOVA rather than repeated t tests.

Whenever your study includes more than two categories or more than one factor, ANOVA usually provides the correct analytical framework.

Key Differences Between These Mean Comparison Tests

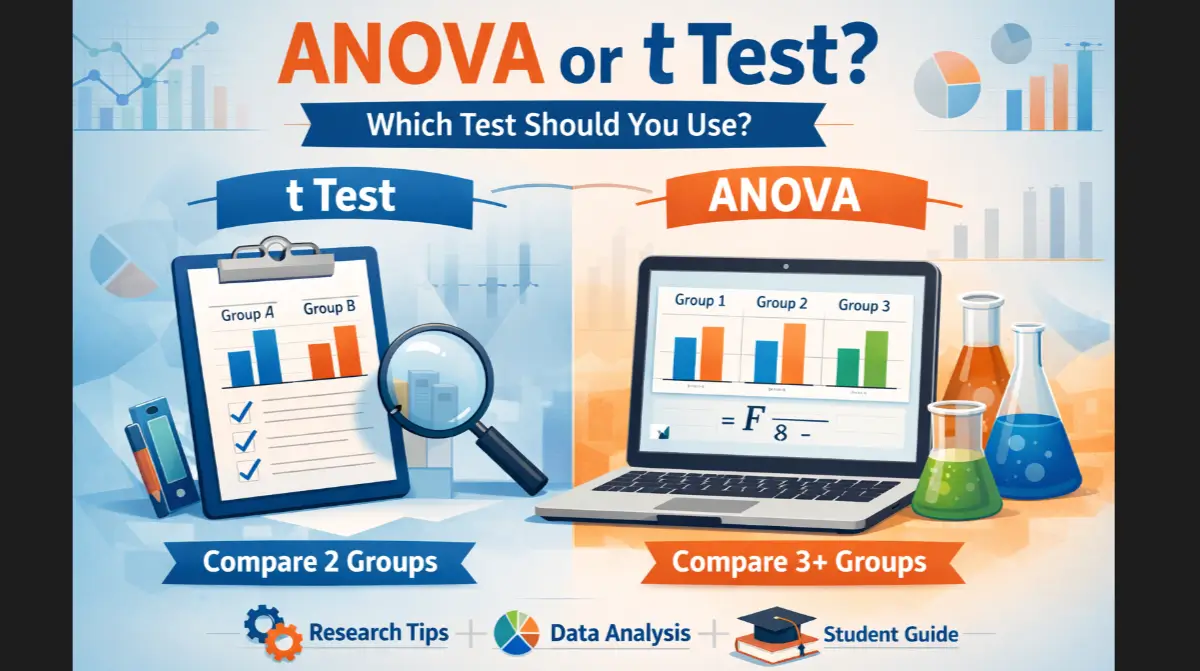

The most important distinction centers on group structure. A t test compares two means. ANOVA compares three or more means or evaluates multiple factors simultaneously. That single rule resolves most confusion in practice.

Model structure also differs. A t test evaluates one comparison at a time. ANOVA builds a variance model that partitions sources of variation across factors and error terms. Because of this structure, ANOVA handles complex experimental layouts more effectively.

Mathematically, a one factor ANOVA with exactly two groups produces the same significance result as a t test. The F statistic equals the squared t value in that special case. Once you exceed two groups or introduce additional factors, equivalence disappears and ANOVA becomes necessary.

In applied research workflows, the decision rule stays simple: two groups lead to a t test, while three or more groups lead to ANOVA.

One Way ANOVA vs t Test

A one way ANOVA examines the effect of a single categorical factor with three or more levels on a continuous outcome. A t test examines the same structure with only two levels. That difference drives the correct choice.

Consider a study that compares test scores across three teaching methods. One way ANOVA fits because the independent variable contains three categories. Running multiple t tests between each pair would inflate error rates and weaken validity.

Now consider the same study with only two teaching methods. In that case, the t test handles the comparison directly and efficiently. Researchers gain no advantage by switching to ANOVA for only two groups.

When to use one way ANOVA instead of a t test depends entirely on how many categories exist under your single factor.

Two Way ANOVA vs t Test

Some studies examine two independent variables at the same time. A t test cannot model that structure. Two way ANOVA evaluates both main effects and the interaction between factors within one coherent model.

Imagine a productivity study that examines training type and workplace setting. Even if one factor has only two categories, the presence of a second factor requires a two way ANOVA design. The model tests each factor separately and also checks whether their combination produces an added effect.

Interaction effects often carry major theoretical importance. Only factorial ANOVA methods can estimate them correctly. A t test cannot capture this relationship.

Whenever your design includes two independent variables, factorial ANOVA becomes the correct analytical path.

Repeated Measures ANOVA vs t Test

Longitudinal and within-subject studies introduce another decision point. A paired t test compares two repeated measurements from the same participants. Repeated measures ANOVA handles three or more repeated measurements.

Suppose a health study records stress levels at baseline, month three, and month six. That structure requires repeated measures ANOVA because more than two time points exist. If the study records only baseline and month six, a paired t test works well.

Within-subject designs benefit from models that account for subject-level correlation. Repeated measures ANOVA reduces unexplained variance and increases statistical sensitivity in multi-timepoint studies.

Not Sure Which Test Fits Your Data?

We help students run the right tests in SPSS and interpret results correctly.

Trusted by graduate researchers.

Chi Square vs ANOVA vs t Test

Mean comparison methods require a continuous dependent variable. Chi square tests handle categorical outcomes instead. This distinction separates the families clearly.

Use chi square when your outcome variable represents counts or categories, such as yes/no responses or preference choices. Use t tests or ANOVA when your outcome variable represents numeric measurements such as scores, ratings, or scale totals.

For example, comparing average satisfaction scores across groups calls for ANOVA or a t test. Comparing response frequencies across categories calls for chi square.

Measurement level of the dependent variable should always drive the first decision step.

Assumptions You Should Check First

Both methods rely on similar assumptions. Researchers should check approximate normality within groups, equal variance across groups, and independence of observations. Paired and repeated designs adjust the independence requirement appropriately.

You can examine normality using plots or formal tests. Variance equality can be tested with Levene’s statistic. When assumptions fail badly, nonparametric alternatives such as Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis offer safer options.

Large samples often tolerate mild normality deviations. Strong variance inequality, however, requires correction methods or alternative tests.

Sound assumption checking strengthens the credibility of your statistical conclusions.

Practical Decision Guide for Test Selection

You can choose the correct test through a short decision sequence. Start with the dependent variable. If it is categorical, use chi square. If it is continuous, continue.

Next, count the number of groups under each factor. Two groups suggest a t test. Three or more groups suggest one way ANOVA. Two independent variables suggest two way ANOVA. More than two repeated measurements suggest repeated measures ANOVA.

Software menus list many options without design guidance. Your research structure, not the software layout, should drive the decision.

Using These Tests in SPSS and Research Projects

SPSS and similar tools provide menu paths for both procedures. T tests appear under compare means with separate options for independent, paired, and one sample designs. ANOVA procedures appear under one way ANOVA or general linear model menus.

Correct variable coding, factor setup, and assumption checks should come before any test execution. Interpretation should include effect sizes and confidence intervals alongside p values for proper reporting.

When uncertainty arises during thesis or survey analysis, methodological alignment matters more than speed. Careful selection and correct interpretation produce defensible results.

Need ANOVA, t Test or Chi-square Done for You?

Send your dataset and research questions. Get analysis and report-ready output.

Fast turnaround • Accurate methods • Revision support included

Conclusion

Choosing between these mean comparison methods depends on design structure, number of groups, number of factors, and measurement timing. T tests handle two-group comparisons. ANOVA handles three or more groups, multi-factor designs, and repeated measures with more than two observations. Chi square covers categorical outcomes.

Researchers who match their statistical method to their design protect the validity of their conclusions and strengthen publication readiness. Proper selection, assumption checking, and interpretation form the foundation of credible quantitative analysis.