A PhD survey demands precision, structure, and methodological rigor from the first question to the final analysis. Your survey design directly affects data quality, statistical validity, and the strength of your thesis conclusions. Weak wording, poor scaling, or flawed logic produces unusable data and forces redesign, recollection, or major revisions during review.

A strong PhD survey starts with clear research objectives, measurable constructs, and properly aligned question types. You need correct sampling strategy, validated scales, logical flow, and bias control built into the instrument. You also need a scoring and analysis plan before you collect a single response. That approach protects your timeline and strengthens your results.

This guide shows you how to build a high-quality PhD survey step by step, from construct mapping and question design to pilot testing and analysis planning, so you collect defensible data and move your research forward with confidence.

Understanding the PhD Survey

What Is a PhD Survey?

A PhD survey is a structured questionnaire used in doctoral research to measure defined variables and test research hypotheses. It follows a documented methodology and uses validated or well-constructed measurement scales, appropriate sampling, and pilot testing to produce analyzable data.

A doctoral survey requires tighter design control than a basic academic questionnaire. The research objectives, constructs, variables, survey items, and statistical analysis plan must match. Each question should map directly to a variable or construct in the conceptual framework.

Researchers design a PhD survey by defining constructs first and then writing items to measure them. Common formats include Likert scales, multi-item measures, indices, and ranking questions. After data collection, researchers test reliability and validity using procedures such as Cronbach’s alpha and factor analysis when required by the study design.

Many PhD surveys use logic features such as branching and conditional display to show only relevant questions to each respondent. The researcher must document the full survey design, measurement logic, and validation steps in the methodology chapter so reviewers can evaluate the instrument.

Why Surveys Are Popular in PhD Research

Surveys are widely used in PhD research because they collect standardized data from many respondents in a structured format. The standardized structure supports statistical analysis and hypothesis testing.

Surveys allow researchers to reach large samples through online distribution, panels, or institutional channels. Larger samples improve statistical power when the sampling method fits the research design. Compared with interviews and experiments, surveys usually require less time and operational setup.

Cost also affects method choice. Survey studies often cost less than lab or field experiments. Closed-ended questions produce pre-coded data, which reduces data preparation time before analysis.

A PhD survey can include both closed-ended and limited open-ended items. Closed items support quantitative testing, while open responses support short qualitative checks or explanations. Because surveys produce structured datasets that fit common statistical methods, many doctoral projects use survey-based designs when constructs can be measured with questionnaires.

Setting Clear Research Objectives

Defining the Research Purpose

The first and most important step in designing a PhD survey is establishing a clear research purpose. This is the foundation upon which the entire survey rests, because without a defined purpose, your questionnaire risks becoming a collection of random questions with no unifying theme. The research purpose answers the big-picture question: What do I want to prove, test, or explore through this study?

At the doctoral level, this is not a vague statement but a precise, academically grounded aim that connects to existing literature and fills a gap in knowledge. For example, if a PhD candidate in education is exploring the effects of digital technology on learning, the research purpose might be to determine how online learning platforms influence student engagement in secondary schools. Having this purpose articulated from the start helps keep the survey aligned with the research objectives, ensures that each question ties back to the dissertation goals, and provides clarity when presenting your work to supervisors or committees. Without a strong purpose, a survey can easily drift off course, leading to data that is irrelevant, unpublishable, or rejected during academic review.

Formulating Hypotheses or Research Questions

Once the research purpose is clear, the next step is to formulate hypotheses or research questions that will guide the survey. Hypotheses are predictive statements that the survey is designed to test. Research questions, on the other hand, are open inquiries that the survey seeks to explore.

At the PhD level, these are not casual questions but carefully framed inquiries that address specific relationships or phenomena. For instance, if your research purpose is to study digital learning tools, a hypothesis could be: “Students who use interactive learning platforms report higher levels of engagement compared to those who do not.” Alternatively, a research question might ask: “What are the perceived challenges of digital platform adoption among secondary school teachers?”

Clearly defined hypotheses or questions act as the roadmap for the survey, ensuring that data collection is focused and meaningful. They also serve as a reference point during analysis, helping you determine whether the evidence supports or challenges your initial expectations. In this way, hypotheses and research questions transform an abstract research idea into concrete, testable pathways.

Identifying the Variables of Interest

No PhD survey can be effective without a thorough understanding of the variables of interest. Variables are the measurable elements that your survey will track in order to test hypotheses or answer research questions. At the most basic level, these include independent variables (the factors you believe influence outcomes), dependent variables (the outcomes being measured), and control variables (factors you need to account for to avoid skewed results). For example, in a study on digital learning, the independent variable might be the frequency of online platform use, while the dependent variable could be student engagement levels. Control variables could include age, socioeconomic background, or prior academic performance.

Identifying variables in advance ensures that your survey questions are not random but targeted to capture precise data needed for your research. It also allows you to select the appropriate statistical tests later, depending on your study design. Vague or undefined variables are a serious weakness, as they compromise both data validity and the strength of your dissertation. Defining your variables clearly makes your research systematic, measurable, and academically credible.

Identifying the Target Audience

Defining Who Your Respondents Are

The success of any PhD survey depends heavily on who your respondents are. It is not enough to simply say you are surveying “students” or “professionals.” A doctoral-level study demands precision in defining the exact population of interest. For example, if your dissertation explores the impact of remote work on productivity, you might target full-time employees working from home for at least six months in the past year. This definition ensures that your data reflects the right group, making your findings more valid and defensible before an academic committee. Defining respondents also helps narrow down your recruitment strategy. Instead of trying to collect random responses, you focus on individuals who fit your research objectives. A well-defined target audience guarantees that the data you collect has both relevance and credibility, and prevents dilution of results with unqualified respondents.

Determining Sample Size

Once you know who your respondents are, the next challenge is deciding how many respondents are enough. In PhD research, the sample size is not arbitrary and must be statistically justified. Too few participants can make your results unreliable, while too many can waste time and resources. Methods like power analysis are often used to calculate the minimum sample size needed to detect significant effects in your data. For instance, if you are conducting a regression analysis, you will need a larger sample compared to running a simple t-test. Your institution’s research guidelines may also suggest minimum respondent thresholds depending on your discipline. Beyond statistics, practical considerations such as budget, time, and participant availability also influence sample size. Addressing sample size early in your research design prevents the frustration of collecting insufficient or unusable data later on.

Recruitment Strategies and Access Challenges

After defining respondents and calculating sample size, the next step is working out how to reach your target audience. Recruitment can be straightforward if you are surveying a readily available group, such as students at your own university. However, it becomes more challenging when your target group is specialized or dispersed. For example, industry leaders, healthcare professionals, or people in specific geographic regions. In such cases, you might need to rely on recruitment platforms like Prolific, Amazon MTurk, or LinkedIn, or even partner with organizations to distribute your survey. Incentives, whether monetary or non-monetary, can significantly improve participation rates. At the PhD level, access challenges are common and must be acknowledged as part of your methodology. Documenting how you overcame these challenges not only strengthens your dissertation but also adds credibility to your data collection process.

Designing the PhD Survey Questionnaire

Key Components of a PhD Research Questionnaire

A PhD research questionnaire is a carefully structured tool designed to capture reliable and valid data that directly supports your dissertation objectives. The first component is demographics, which may seem basic but are essential for contextualizing findings. Information such as age, gender, education, or work experience helps segment responses and identify patterns across different groups. The second component is the inclusion of core research variables. These questions are crafted specifically to test your hypotheses or address your research questions. Without them, the survey risks drifting off-topic. Control variables are equally important, as they allow you to account for external factors that may influence outcomes, such as industry type or job role. Finally, a strong questionnaire balances open and closed questions. Closed questions allow for quantifiable analysis, while open questions capture nuanced insights that numbers alone may not reveal.

Principles of Good Question Design

Even the most well-thought-out research design can fall apart if the survey questions are poorly worded. At the PhD level, clarity is non-negotiable. Each question must use precise language to avoid ambiguity or misinterpretation. For example, asking “Do you like AI at work?” is vague, while “To what extent do you agree that AI tools improve your efficiency at work?” is specific and measurable.

Neutrality is another key principle; questions should never be framed in a way that pressures respondents toward a particular answer. Bias in wording can invalidate your data and compromise the credibility of your research. Every item in the questionnaire should also maintain relevance by mapping directly to your research objectives. If a question does not contribute to answering your hypotheses or research questions, it should be removed. Finally, logical structure enhances respondent engagement. Starting with general questions and gradually moving to more detailed or sensitive items creates a natural flow, reduces dropout rates, and improves the quality of responses. Adhering to these principles ensures that your PhD research questionnaire generates valid, reliable, and ethically sound data.

Example: Sample Questionnaire for PhD Research – Impacts of AI in the Workplace

Below is a professional sample PhD survey questionnaire with 15 expert-level questions. The research topic is: Impacts of AI Adoption in the Workplace on Employee Productivity and Job Satisfaction.

A: Demographics

- What is your age group? (Under 25, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55+)

- What is your current job role/position? (Open text or predefined roles)

- How many years of professional experience do you have? (0–2, 3–5, 6–10, 10+)

B: AI Adoption and Use

- How frequently do you use AI-powered tools in your daily work? (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always)

- Which AI applications are most relevant to your role? (e.g., Chatbots, Data Analytics, Process Automation, Generative AI, Other)

- On a scale of 1–5, how easy have you found it to adapt to AI tools in your work?

C: Productivity and Efficiency

- To what extent do you agree that AI tools have improved your productivity? (Strongly Disagree – Strongly Agree)

- Which aspects of your work have improved most due to AI integration? (Speed, Accuracy, Decision-making, Collaboration, Other)

- Have AI tools reduced repetitive or mundane tasks in your role? (Yes/No, with optional explanation)

D: Job Satisfaction and Concerns

- How has AI impacted your overall job satisfaction? (Much worse – Much better)

- Do you feel AI creates opportunities for career development in your field? (Yes/No/Unsure)

- What concerns, if any, do you have about AI adoption in your workplace? (Open-ended)

E: Organizational and Ethical Implications

- Does your organization provide adequate training on AI tools? (Yes/No/Partially)

- How confident are you that your organization uses AI ethically and transparently? (Not confident – Very confident)

- In your opinion, what should organizations prioritize to ensure AI benefits employees as well as the business? (Open-ended)

PhD Survey Methodology

Fundamentals of Survey Research Methodology

At the PhD level, survey methodology is not just a technical detail but a central component of your research design that directly determines the validity and reliability of your findings. A strong survey methodology starts with the research design, which defines how your data will be structured. Cross-sectional designs capture a snapshot of opinions or behaviors at one point in time, whereas longitudinal surveys track changes across months or years. Experimental designs, while less common in social sciences, may involve manipulating conditions to study causal relationships. Selecting the right design requires a careful alignment with your dissertation’s objectives.

Next, the sampling strategy determines who will participate in the study. Probability sampling (such as random or stratified sampling) ensures that every member of the population has an equal chance of selection, which improves generalizability. In contrast, non-probability sampling (such as convenience or snowball sampling) is more practical but may introduce bias. PhD researchers must justify their choice by weighing feasibility against statistical rigor.

The data collection method also shapes the results. Online surveys are efficient and cost-effective, but they risk excluding populations with limited internet access. Paper-based or telephone surveys may provide better inclusivity but require more resources. Mixed-mode approaches can combine strengths while mitigating weaknesses. Finally, a data analysis plan must be mapped out in advance. This often involves statistical techniques like regression, correlation, factor analysis, or structural equation modeling. Defining the methodology in this way ensures that every step of the survey process is transparent, replicable, and defensible when reviewed by examiners or committees.

Writing the PhD Survey Methodology Section

The methodology chapter of a PhD dissertation demands close scrutiny because it justifies how the researcher collects, analyzes, and interprets data. In this section, the researcher should do more than state that they used a survey. They must explain why they chose surveys instead of other methods such as interviews, focus groups, or experiments. The justification should emphasize the strengths of surveys, including scalability, quantifiability, and efficiency, while also addressing their limitations and explaining how the researcher managed them.

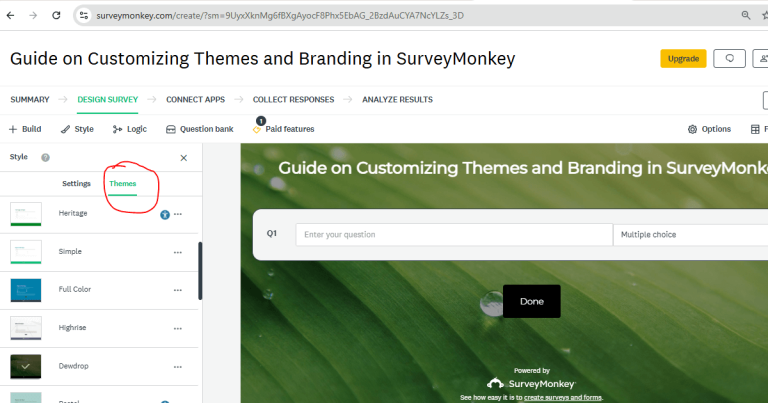

Equally important is the description of the survey platform. PhD students must specify whether they used tools such as SurveyMonkey, Qualtrics, or Google Forms, and why that platform was appropriate for their study. Some platforms offer advanced branching logic or anonymity controls, while others may be chosen for cost-effectiveness. Detailing this ensures transparency and reproducibility.

Another vital component is the explanation of sampling procedures. Researchers must describe who was surveyed, how participants were recruited, and why the chosen sample size is sufficient. This includes referencing statistical calculations like power analysis, which demonstrates that the sample is large enough to detect meaningful effects. The methodology section must also discuss pilot testing, outlining how a smaller version of the survey was trialed to detect errors in logic, clarity, or structure before full deployment.

Pilot Testing Your Dissertation Survey

Pilot testing functions as a controlled trial run of the PhD survey. A small representative group completes the questionnaire before full deployment. This process reveals clarity problems, logical errors, and technical faults.

Pilot respondents often identify confusing wording, missing response options, and survey fatigue points. Branching logic and skip paths can be verified during this stage. Timing estimates also become more accurate.

Revisions based on pilot feedback improve measurement reliability and respondent experience. Many institutions expect pilot evidence in PhD survey methodology documentation because it demonstrates quality control.

Ethical Considerations in PhD Surveys

- Informed Consent – Every respondent must be made fully aware of the purpose of the research, what their participation involves, and how their data will be used. This usually requires a clear consent form or opening statement in the survey. Respondents should also know they can withdraw at any time without penalty.

- Confidentiality – Protecting the personal data of participants is a critical ethical responsibility. This often means anonymizing responses so that individuals cannot be identified, encrypting stored data, and ensuring results are reported in aggregate. By maintaining confidentiality, you protect the integrity of your study and uphold participant trust.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval – Most universities require formal ethics approval before a PhD survey can be distributed. The IRB evaluates whether your methodology respects participant rights and meets academic standards. Without this approval, even the most well-designed research could be rejected or invalidated by your institution.

- Avoiding Bias or Harm – Researchers must take extra care when working with vulnerable populations (e.g., children, patients, minority groups). Questions must be framed neutrally to avoid leading respondents, and sensitive topics should be handled with empathy. The goal is to collect accurate data without causing psychological, emotional, or professional harm.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in PhD Survey Research

- Designing questions that don’t align with research objectives

- Using biased or leading wording

- Failing to pretest the survey

- Ignoring sample size requirements

- Collecting too much irrelevant data

- Poorly writing the PhD survey methodology chapter

When to Hire PhD Survey Experts

Even the best doctoral candidates sometimes need professional support. Hiring PhD survey experts like MySPSShelp.com ensures:

- Transparent pricing (no hidden costs)

- Affordable packages for students

- Multiple revisions until satisfaction

- On-time delivery of survey design and analysis

- High-quality methodology writing that meets PhD standards

Advanced Considerations in PhD Survey Research

- Mixed-method surveys combining quantitative and qualitative approaches.

- Longitudinal PhD surveys that track changes over time.

- Cross-cultural surveys with translation and cultural adaptation.

- Digital integrations with tools like Mailchimp, Teams, or Zoom.

Building a Successful PhD Survey

A PhD survey is about collecting reliable data that strengthens your dissertation. By carefully defining objectives, selecting the right methodology, designing strong questionnaires, and ensuring ethical standards, you can produce research that is both credible and impactful.

And when the process feels overwhelming, partnering with survey experts like mySPSShelp.com guarantees professional, accurate, and stress-free outcomes.

Ready to design your PhD survey? Hire an expert today and get it right the first time.